From St. Lucia to St. Louis

Growing up in St. Lucia, Dr. Tessa Burch-Smith was surrounded by native orchids and lush tropical plants - but it wasn’t until her undergraduate experience that she began to appreciate them.

“In the Caribbean, you're constantly fighting with plants to gain a foothold,” explains Tessa. “You clear a piece of land and come back two days later to find more plants growing. It was a constant battle.”

While Tessa was uninterested in plants, she was fascinated by science from an early age. When she was in graduate school studying molecular and cell biology, she learned more about plant science, and how much is still unknown about what happens inside plants. “As humans, we spend a lot of time manipulating plants for our benefit,” says Tessa. “What drives my interest is to actually understand the inner workings and the processes behind what facilitates those traits that we as humans benefit from or desire.” The more that Tessa learned about plants, the more interested she became.

Today, Dr. Tessa Burch-Smith is an Associate Member and Principal Investigator at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center.

Plasmodesmata: Understanding How Cells Communicate

At the Center, Tessa and her lab work to understand how plant cells communicate with each other through intercellular channels called plasmodesmata (PD). Plants are actually a vast network of interconnected cells that exchange essential molecules like sugars, proteins and RNA through PD during growth and development. And viruses exploit PD channels to move from cell to cell as they spread through plants. Tessa and team are shedding light on two important plant biology topics: how different parts of a plant exchange signaling molecules and metabolites, and how viruses interact with their hosts to cause disease.

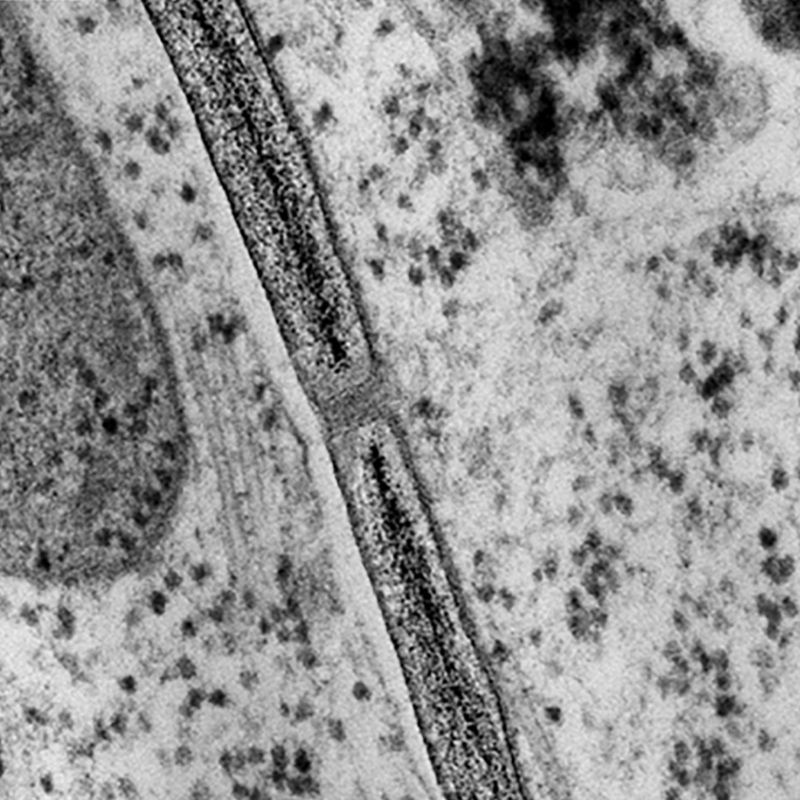

TEM image of a plasmodesmata

Plasmodesmata cannot be seen by the human eye without the help of electron microscopy. As a result, Tessa and her lab collaborate with Dr. Kirk Czymmek and the Advanced Bioimaging Laboratory. Electron microscopy allows investigation into how PD channels form between cells, the structure of PD, as well as PD special functions. In 2021, the Advanced Bioimaging Laboratory acquired a state-of-the-art transmission electron microscopy to enable the Burch-Smith lab to create nanometer scale three-dimensional reconstructions of PDs to aid in answering key questions. Since Tessa and her lab also want to understand the movement of molecules between cells, they also plan to use super-resolution light microscopy to see single molecules that are part of PDs and how they behave in living cells.

Developing More Efficient Plants

An understanding of PD would allow scientists to control how plants distribute resources to their cells, resulting in a more efficient plant. “For instance, if we want to eat the fruits of a plant, we could redirect the plant to put more resources towards producing larger fruit instead of growing taller,” explains Tessa. If Tessa’s research is successful, it could also allow plant scientists to control virus infections. By understanding how a virus moves through the plant via PD, it could be possible to slow the movement of a pathogen through the plant, eliminating the disease completely or preventing a more severe infection.

Ultimately, Tessa’s research could enable farmers to produce more food with a smaller environmental footprint, with less risk of losing yield to diseases. As climate change continues to impact agriculture and farming communities around the world, Burch-Smith’s research could have an impact on food security in the future.

Creating Opportunity and Community in Plant Science

Tessa Burch-Smith is also committed to creating inclusive opportunity and community in plant science. “I think there are lots of people out there with lots of untapped potential who would make great scientists,” says Tessa. “One of my goals is to make science feel more attainable. We need to have people with varied interests and outlooks in science so that we can produce outcomes that are varied.” Tessa is proud of her lab for acting on this goal. In nearly ten years at the University of Tennessee, Tessa and her lab have hosted over 40 undergraduates, many of whom have gone on to graduate school and even medical school. “I think that's one of the major strengths of my group. We're very diverse in composition, skill level and origins. I'm really proud of that,” she says.