The Danforth Center Prairie: A Living Lab for Plant Science and a Biodiversity Boon for St. Louis

Whether you’re a regular visitor at the Danforth Plant Science Center or someone who’s only passed by on Olive Boulevard, the six-acre prairie is likely one of the first things you’ve noticed about our campus. But it wasn’t always the landscape it is now. For years, our front lawn was just that: a classic lawn.

In 2015, the Danforth Center decided to make a change and began the process of converting the turf grass to a tallgrass prairie.

Now, nearly 10 years later, the prairie has become a living lab for plant science; a favorite walking path for the community; and an ecosystem for urban wildlife. Earlier this month, Member and Robert E. King Distinguished Investigator Elizabeth A. “Toby” Kellogg, PhD, and Entomologist, Senior Research Scientist, and Principal Investigator Bala P. Venkata, PhD, spoke about what motivated the change, the work that went into the reconstruction process, and the benefits we’re seeing now.

Entomologist, Senior Research Scientist, and Principal Investigator Bala P. Venkata, PhD (left), and Member and Robert E. King Distinguished Investigator Elizabeth Ann “Toby” Kellogg, PhD (right), spoke with the Danforth Center community at a special event celebrating our six-acre prairie reconstruction in honor of Earth Month.

Rich Roots: The Past and Perks of Prairies

Toby began the talk with a brief history of prairie ecosystems and the importance of restoring them. She shared that much of North America was covered by tallgrass prairie before colonization by European settlers. This ecosystem was common in Missouri, including in what is now the Greater St. Louis area, and it was an important one. Prairie grasses have enormous, dense root systems that sequester carbon—up to 1.7 metric tons per acre each year. This encourages the growth of beneficial bacteria and fungi and produces exceptionally healthy, fertile soil.

“But we all know what happened,” Toby said. That healthy soil made for excellent farming, but this led to the widespread removal of these grasses as they were replaced with agricultural crops. Today, the tallgrass prairie is one of the most endangered ecosystems in North America. Less than 1% of the original prairie remains.

In recent years, prairie preservation and reconstruction have gained traction. Because so much of the original prairie is long gone, opportunities for preservation are important but limited, so reconstruction is an imperative piece of the puzzle. In 2015, with our mission to improve the human condition through plant science and vision to preserve and renew the environment in mind, the Danforth Center set out to become a part of this movement.

Elizabeth “Toby” Kellogg shared this photo of what the Danforth Center’s landscape used to look like before its reconstruction. The change to a tallgrass prairie has made the space both more eco-friendly and more cost-effective to maintain.

Bringing Back Biodiversity: What It Took to Restore the Prairie

“Contrary to what it might seem, prairie reconstruction isn’t just letting the grass grow,” Toby explained. There is much more that goes into a proper ecological reconstruction.

First, non-native turf grasses and other unwanted vegetation must be destroyed. To achieve this, the Danforth Center removed all the topsoil from the lawn, scraping down to the mineral soil.

Next, the land had to be replanted. “We used a custom mix provided by Hamilton Native Outpost, Missouri Native Wildflowers, and Scott Woodbury of Shaw Nature Reserve,” Toby said. No fertilizer or topsoil was added. Instead, the new plantings got a natural boost. Some seeds were coated with a mix of beneficial fungi, and annual ryegrass was planted as a cover crop to maintain soil health while the native grasses established themselves.

From there, it became a waiting game. In the months following the planting, the new prairie needed some extra care. Caretakers checked for seedlings of native plants and logged what they found. Weeds were removed, the ryegrass was mowed, and some areas were overseeded. The hard work paid off.

“Within a year, insects and birds reappeared,” Toby said. What was once just an ordinary lawn has now become an ecosystem for native wildlife.

Pictured above: After the prairie was seeded, it was monitored to track the progress of the native plants’ return. Within just a couple years, major progress was already evident.

A Bounty of Benefits

Almost a decade into the prairie reconstruction, the benefits of the prairie have been astounding.

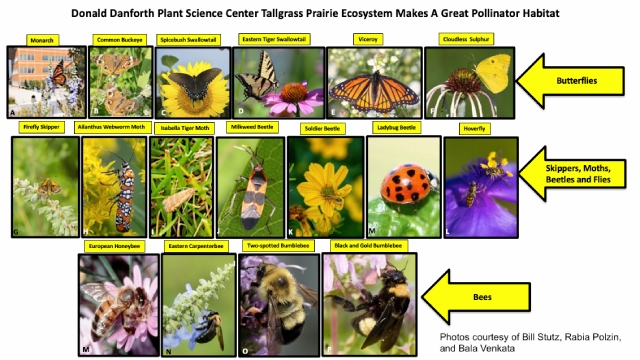

The return of insects has been particularly impressive. Bala, who is an entomologist, spoke to the extraordinary amount of life to be found in the prairie. From 2019 to 2022, Bala and his team documented insect biodiversity in the Danforth Center prairie and found a remarkable diversity of insects, from native bees and moths to honeybees to migrating monarchs.

“Butterflies, skippers, moths, and bees are indicative of a functioning prairie habitat,” Bala said. “There is a basic reconstruction ecology hypothesis of ‘if you build it, they will come.’ Reconstruction efforts provide nesting sites and floral resources to achieve stable and diverse insect populations.”

Supporting declining insect populations is crucial. Beyond their benefit to the environment, insects are a necessary part of the pollination process and, therefore, a necessary part of the food we grow. Bala shared that pollinators have an estimated impact of about $577 billion on agriculture each year.

The ecological and agricultural benefits are not the only advantages of a prairie reconstruction. “At the time that we made the decision to undergo this reconstruction, the Danforth Center was spending around $45,000 a year on landscaping and lawn maintenance,” Toby said at the end of the presentation. “Now, we are spending just a third of that.”

A Bright Future: Continued Care for the Prairie

Looking to the future, the Danforth Center prairie is here to stay, and we are continuing to invest the work it takes to keep it thriving. One way we’re doing this is through controlled burns.

Pictured above: We conducted our first controlled burn in February 2024. Within a matter of weeks, new, green growth was sprouting up from the ashes.

This past winter, we were able to conduct our first controlled burn. Using fire as an ecological restoration tool can help encourage seed germination, soil health, and native species control. Historically, fire resulting from lightning strikes was a natural part of Missouri ecosystems. It was also used by indigenous communities who lived here as a land management strategy and agricultural tool. Because of this long history, many Missouri-native plants are adapted to fire, while nonnative invasives can’t handle the heat.

In the two recently burned acres of Danforth Center prairie, blue false indigo blooms in April 2024.

This year, two of the six acres were burned as a part of this strategy. Toby shared that a plan has been developed to execute a prescribed burn on rotating two-acre sections of the prairie each year, so that each section will be burned every three years.

We’re proud to continue this work to bring an urban oasis to the St. Louis area, and we invite you to stop and take a walk the next time you’re passing by.